Here we look at the many threats impacting our environment, in particular our native ecosystems and biodiversity. The threats often occur in combination and in doing so build on each other. Together they can mount up to become a very powerful force pushing the environment towards degradation, or even species towards extinction, and therefore require a comprehensive conservation strategy to deal with.

There is a simple acronym to memorise the human induced threats- “HIPPO”: Habitat change, Invasive species, Population growth, Pollution and Overharvesting. We must also add climate change and natural disasters, which are human influenced, natural threats.

Habitat change and degradation: For land this mainly refers to forest loss or deforestation and for the sea this is loss of marine ecosystems such as coral reefs, sea grass beds and mangrove areas, mainly for development, or agriculture. Samoa had a deforestation rate approaching 2% per annum in the 1980s but this has slowed significantly. Forest cover was around 60% of Samoa’s land area in 1999 and declined to 58.3% in 2013, a drop of only 1.7% in 14 years.

Habitat loss from development is a major cause of environmental degradation in Samoa such as here for a subdivision in the Upper Gasegase catchment.

When you consider that Samoa at one time was almost completely covered in rainforest, except on recent lava flows, this is an overall loss of around 40% of the original forest cover. Particularly impacted are the mangroves, and the coastal and lowland rainforests which have mostly been converted to settlements or agricultural plantations. Whole groups of species that are adapted to such coastal forests, such as Pau (Manilkara samoensis) and Ifilele (Moluccan Ironwood) are now threatened too. We do not have good data on the loss of marine habitats but do know that coral reefs and mangroves have been heavily impacted by development or reclamation and weakened by other threats such as from pollution or sedimentation.

Many hectares of rare lowland rainforest were bulldozed to create the new town at Salelologa in 2001.

Invasive species: Now around half of our animals and plants are introduced species that were brought in accidentally or on purpose by people. Many of these introduced species have spread into our native ecosystems and are called “invasive”. They tend to have few if any natural predators and can therefore breed rapidly and disperse quickly. There are numerous examples, but invasive species that have serious impacts are often called “ecosystem transformers” and include plants such as Tamaligi (Albizzia species), Fa’apasi (African tulip), Pulu vao (African rubber) and Pulu mamoe (Panama rubber), invasive mammals such as rats, cats and pigs, invertebrates like Sisi Afelika (African snails) and Rhinoceros Beetles and birds such as Myna birds and many others. Most of our native birds are severely impacted by rats and cats so that many are now restricted to offshore islands, deep forest and inaccessible places like treetops, where cats and rats may not get to them so easily.

Rats like this Ship Rat (Rattus rattus) are one of the most serious invasive pest species in the world and impact many native Samoan species, especially birds, by eating eggs and chicks. They were introduced by humans so are not native to Samoa.

It is important to note that the “quality” of our ecosystems is highly influenced by invasive species, so that it’s not just the “quantity” or percentage of native ecosystem cover that matters (e.g. percentage of land that is rainforest), but also the cover of that ecosystem that is dominated by invasive species (e.g. percentage of the forest that is dominated by Tamaligi). Ecosystems that are dominated by invasive species tend to not only have fewer species overall, but also to be less stable and resilient to other threats such as cyclones, erosion or fire. Proof of this can be seen after cyclones when the rivers are often blocked by fallen or broken invasive trees like Tamaligi.

Pollution and waste: Many of our native ecosystems are heavily impacted by pollution from human, and agricultural waste- such as seepage from septic tanks, industrial waste including heavy metals, plastics and residue from agricultural chemicals such as fertilizers, insecticides and herbicides as well as from sedimentation from coastal development and soil erosion caused by forest loss in watershed areas. Some of this pollution gets into the food chain and can accumulate in crabs, fish and shellfish. Ultimately the chemicals and waste we put into the environment may be consumed by humans who are at the top of the food chain with potentially severe health impacts in terms of cancers and other diseases.

Batteries such as these are often not disposed of properly and can release heavy metals such as cadmium into the environment and that potentially get into the food chain.

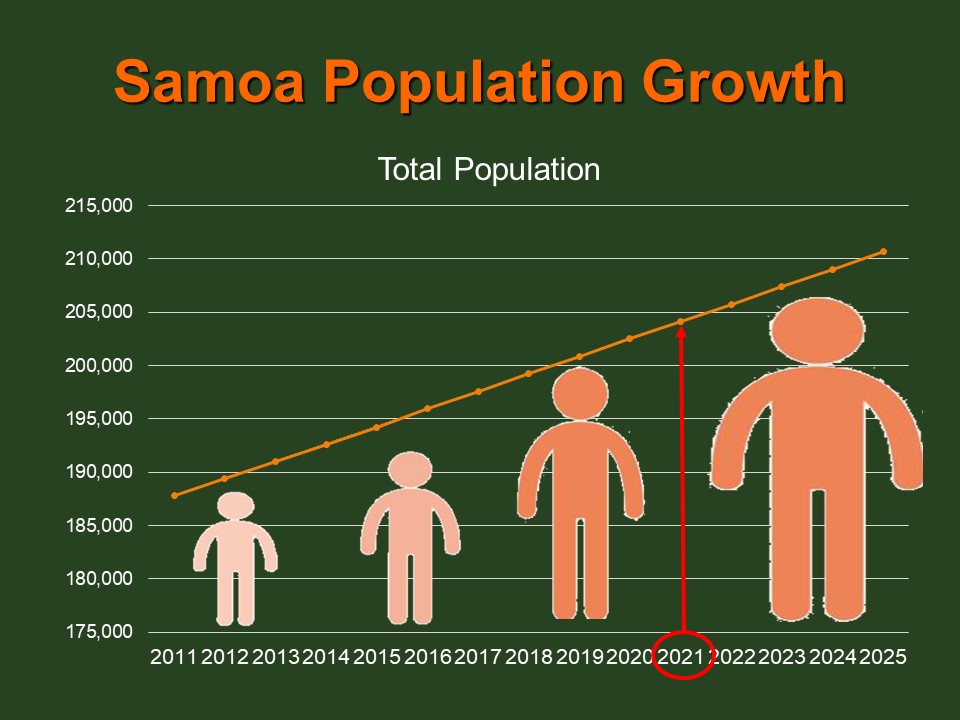

Population growth: Just prior to the Spanish flu’s arrival in Samoa in 1918, Samoa’s population was around 40,000 people. Now it is around 205,000 people, a fivefold increase in 100 years. More people not only need more space to live and grow food, they also need a lot more food and other resources for subsistence, and increasingly, for cash. When you consider the changes in our technology with for example guns replacing snares to catch pigeons, bulldozers and chainsaws to clear land rather than adzes and scuba gear now used to catch lobsters, the human impact on the environment is greatly increased. Luckily our population growth has slowed significantly due to a falling birth rate and steady emigration. We can now focus more on the quality of life for all Samoans, rather than promoting unsustainable population growth.

Samoa’s population continues to rise and reached 205,000 in 2021, although growth has slowed over the past few decades due to a declining fertility rate and continued emigration.

Overharvesting: Many native species have been harvested beyond their ability to replenish or reproduce themselves. Theoretically native species can be harvested sustainably indefinitely if careful controls are put in place on numbers, seasons and sizes of harvested species. However, calculating what the sustainable rate is and the other rules that go with it, is a complex science and depends on many factors. In an attempt to put controls on harvest levels there are many village and national laws and regulations over harvest sizes of various species of animals and outright bans on others. For example, there are outright national bans on hunting endemic birds including all our native pigeons and flying foxes in Samoa and size limits on many fish, mollusc and crustacean species.

The harvest of legally protected species such as Manumea (Tooth-billed pigeon), is unfortunately still common in Samoa. There may only be 200 Manumea left making her Critically Endangered. Photo by Art Whistler.

Enforcing these laws however, is problematic, and many species continue to be harvested well beyond their sustainable levels, or in damaging ways. Consider the damage done to the coral reefs when Palolo worms are harvested. Other examples of overharvest include many fish and shellfish and even some plants such as Ifilele (Moluccan ironwood- used for kava bowls). Also, sometimes species like Manumea, are accidentally caught as “bycatch” when the actual target is another species (in this case Lupe or Pacific Pigeon). The end result is the same, a declining population and potential extinction.

Natural disasters and climate change: On top of all the threats that humans are directly responsible for as per the threats described above, are the natural threats of cyclones and storms, fire, flood, drought, landslips, earthquakes and tsunamis. All of them, apart from the last two, are also influenced by human behaviour and actions and worsened by climate change. These threats can be the most serious of all and can wipe out whole ecosystems and cause many species extinctions in one fell swoop. Species such as the Tagiti or Sheath-tailed bat are thought to have gone extinct because of repeated cyclones and insufficient recovery time in between events. Particularly threatened by climate change are the coastal areas that will be inundated by sea level rise or saltwater intrusion, the coral reefs that may suffer bleaching and death from temperature rise or ocean acidification and the cloud forests where species adapted to cool, wet conditions will have no-where to go if the temperature rises or rainfall patterns change. One of the challenges we face in Samoa that makes all our threats even harder to manage is that our islands are particularly vulnerable because of their small size, isolation and limited natural resource base. We simply don’t have the land and marine resources to make too many mistakes. While we cannot remove all environmental threats, we can minimize our contributions to many of them by reducing our environmental impact.

Cyclones can devastate natural ecosystems such as here at Mt Vaea after Cyclone Evan in 2012. Climate scientists say that cyclones will get bigger but perhaps less frequent in Samoa’s future climate.